Errors

To view this content, buy the book! 😃🙏

Or if you’ve already purchased.

Errors

In Nullability, we’ll see what a thrown error looks like to the client, and we’ll look at how data in the response changes based on whether fields are nullable. In Union errors we’ll use the union type to return errors instead of throwing them. In formatError we log and mask errors, in Error checking we go through all the other errors we might want to check for or handle, and in Custom errors we create our own type of Apollo error.

Nullability

If you’re jumping in here,

git checkout 11_0.2.0(tag 11_0.2.0, or compare 11...12)

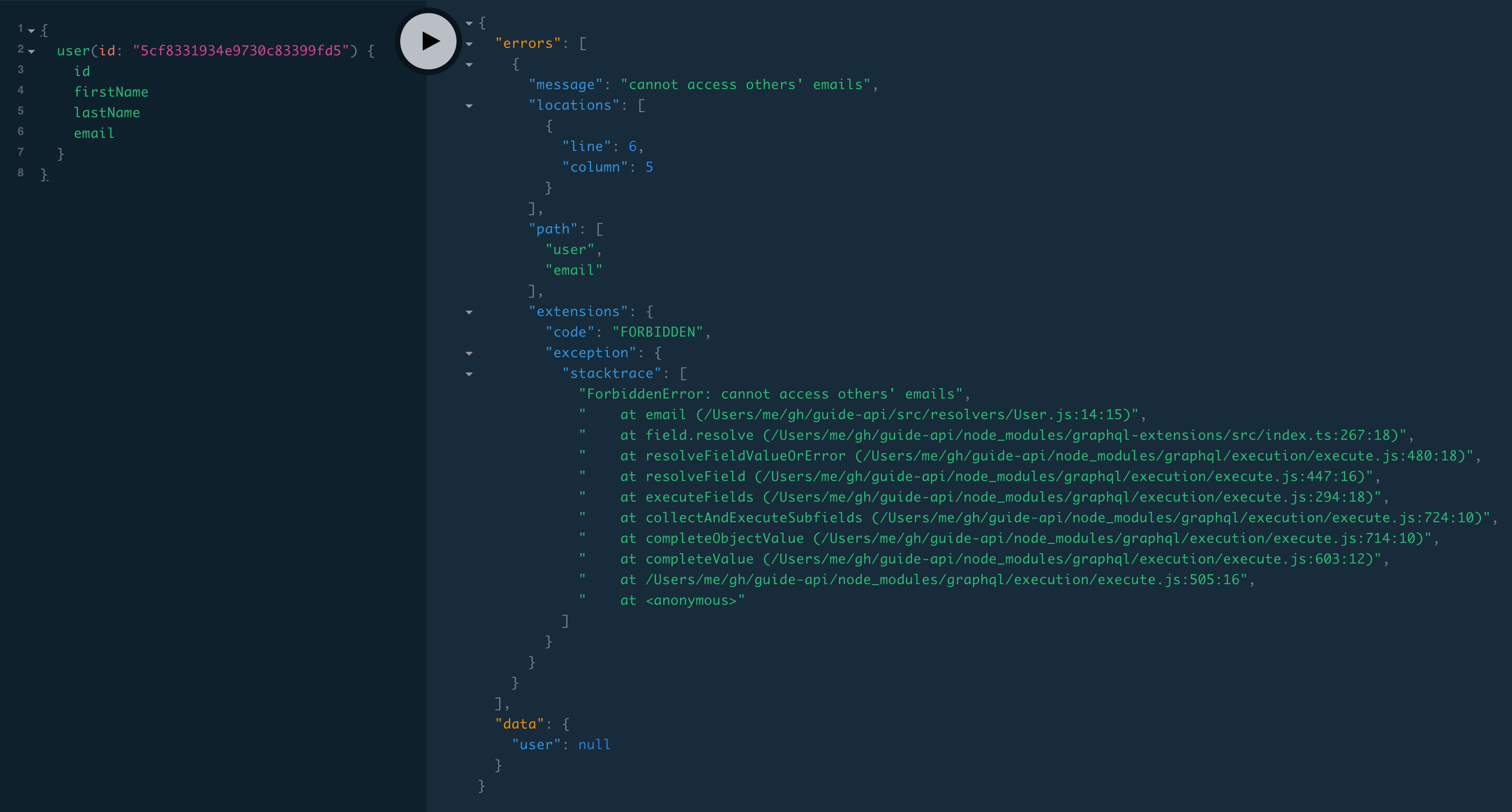

In the last section, we throw an error when the client requests an email address and they’re either not logged in or it’s not their email. Let’s see what that error looks like by making a user query without an authorization header:

{

user(id: "[id of a user in our database]") {

id

firstName

lastName

email

}

}We get an errors array with one item (an object with fields message, locations, path, and extensions) and null data:

{

"errors": [

{

"message": "cannot access others’ emails",

"locations": [

{

"line": 6,

"column": 5

}

],

"path": [

"user",

"email"

],

"extensions": {

"code": "FORBIDDEN",

"exception": {

"stacktrace": [

"ForbiddenError: cannot access others’ emails",

...

]

}

}

}

],

"data": {

"user": null

}

}- The

messagematches the string we created our error with:

throw new ForbiddenError(`cannot access others’ emails`)- The

pathsays the error occurred in theemailfield of theuserquery, andlocationsgives the line and column number of theemailfield in the client’s query document. extensions.codeis set toFORBIDDENby theForbiddenError()we’re using. If we use a plainError(throw new Error("cannot access others’ emails")), thenextensions.codewould beINTERNAL_SERVER_ERROR.- The stack trace is included unless

NODE_ENVis set to'production'.

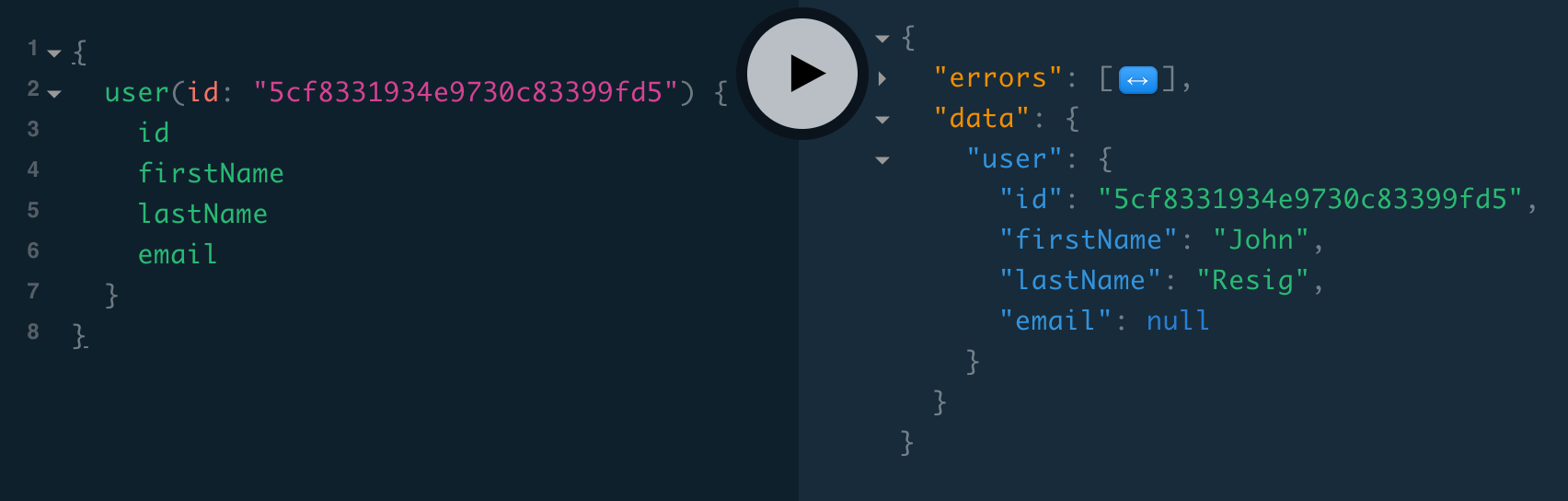

It would be nice if the server returned the rest of the user data we requested (id, firstName, and lastName) instead of just null. The reason it doesn’t is User.email is non-nullable (String!), so a null cascade occurs: without an email value, the server isn't able to return a whole valid User type, so it returns null for the whole Query.user field. If we make it nullable by removing the !, throwing an error from the User.email resolver will return null just for the email field—the server will still return the rest of the User fields:

type User {

id: ID!

firstName: String!

lastName: String!

username: String!

email: String

...

}

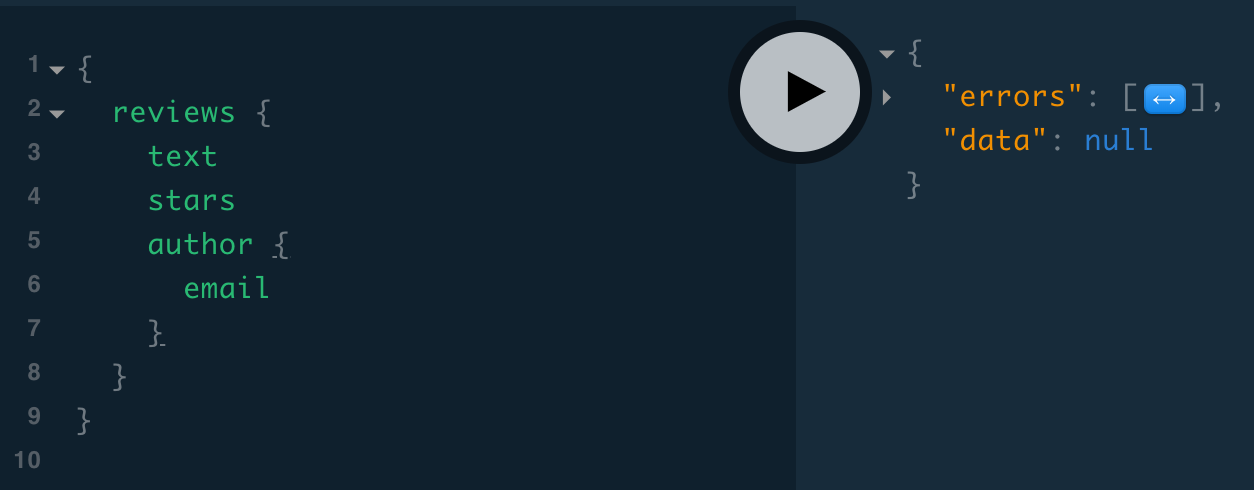

💃 This is a great improvement, especially since in the non-nullable case, a thrown error results in not just null for the user, but anything at a higher level as well! For example, here’s a reviews query requesting a non-nullable email:

{

reviews {

text

stars

author {

email

}

}

}

Apollo server tries to return null for email, but it’s non-nullable, so then it tries to return null for Review.author, but it’s non-nullable, so then it tries to return null for the review, but the review is non-nullable and the list of reviews is non-nullable so we don’t even end up with "data": {"reviews": null}—we just get "data": null!

So when we throw an error for a certain field but still want the client to get the rest of the data, we want to remember to make that field nullable. ❌❗

Union errors

If you’re jumping in here,

git checkout 12_0.2.0(tag 12_0.2.0, or compare 12...13)

As mentioned in the Authorization section, an alternative to throwing an error is returning null. The downside is the client can’t determine whether the server is returning null because there’s no data or because the client doesn’t have access to it. It might be helpful to know they don’t have access so that they can prompt the user to log in.

When a field’s type is an object type, an alternative to returning null from the resolver is returning an error object. We can do this by changing the type to a union. Instead of:

type Query {

item(id: Int!): Item

}

type Item {

id: Int

name: String

}we can do:

type Query {

item (id: Int!): ItemResult

}

type Item {

id: Int

name: String

}

type ItemError {

reason: String

}

union ItemResult = Item | ItemErrorNow the item query resolver is able to return either an Item or an ItemError. This query:

{

item(id: 1) {

__typename

... on Item {

name

}

... on ItemError {

reason

}

}

}can return either of these two JSON responses:

{

"data": {

"item": {

"__typename": "Item",

"id": 1,

"name": "GraphQL hacky sack"

}

}

}{

"data": {

"item": {

"__typename": "ItemError",

"reason": "This item has been discontinued."

}

}

}Why do this? It can be easier for the client to handle the errors if they’re inline in the "data" attribute of the JSON rather than the "errors" attribute. For example, imagine a searchUsers query that returned a long list of users. If we wanted the client to be able to show some information about deleted or suspended users, and we threw errors for each one, the client would have to go through an array of "errors" in the JSON response and match them up with holes in the data.searchUsers results. Further, they would have to be familiar with what type of errors are thrown and the format of the error data. Versus if we document in the schema the types of expected errors and return them from resolvers, clients know what data possibilities to expect, and they can smoothly iterate over just the data.searchUsers JSON array that they get.

Expected is highlighted because unexpected errors (like an unauthorized error or database failure) are usually kept as thrown errors, for the client to handle outside of its normal process of presenting expected data on the screen.

Let’s implement this searchUsers query to see what it looks like. As usual, we’ll start with the schema:

extend type Query {

me: User

user(id: ID!): User

searchUsers(term: String!): [UserResult!]!

}

type DeletedUser {

username: String!

deletedAt: Date!

}

type SuspendedUser {

username: String!

reason: String!

daysLeft: Int!

}

union UserResult = User | DeletedUser | SuspendedUserA UserResult union type can be either a User, DeletedUser, or SuspendedUser, each of which have a __typename and username but have different other fields. Let’s implement the searchUsers resolver next:

export default {

Query: {

me: ...

user: ...

searchUsers: (_, { term }, { dataSources }) =>

dataSources.users.search(term)

},We take the search term parameter and pass it to a search() method, which will talk to the database:

export default class Users extends MongoDataSource {

...

search(term) {

return this.collection.find({ $text: { $search: term } }).toArray()

}

}$text: { $search: term } does a text search of the users collection. For it to work, we need to create a text index, which includes all the fields we want to search—in this case, the name and username fields. In MongoDB, we usually use the collection.createIndex() method, which checks if the index already exists, and creates it if not. It would be nice to put the command in the same file as our search() method so that it’s easy to see which fields are being searched. One method we know will get called is the constructor, so we can put it there:

export default class Users extends MongoDataSource {

constructor(collection) {

super(collection)

this.collection.createIndex({

firstName: 'text',

lastName: 'text',

username: 'text'

})

}

...

}We’re currently instantiating this data source with:

new Users(db.collection('users'))so in order to maintain that functionality, we need to take that object argument collection and pass it to super().

A new

Usersobject is created for every request, which is far more often than we need to be callingcreateIndex()—once at server startup would be sufficient—but the performance impact is miniscule, so we needn’t worry about it until we’re at Google scale 😄.

Now our search() method returns a list of users, but they’re all normal users—we don’t have any suspended or deleted users yet. Let’s create three users in our database, all with the same first name so that they come up in a single search:

If you generated your own secret key, use that. It’s located in your

.envfile.

mutation {

createUser(

user: {

firstName: "John"

lastName: "Resig"

username: "jeresig"

email: "[email protected]"

authId: "github|1615"

}

secretKey: "9e769699fae6f594beafb46e9078c2"

) {

firstName

lastName

}

}mutation {

createUser(

user: {

firstName: "John"

lastName: "Smith"

username: "jsmith"

email: "[email protected]"

authId: "github|1"

}

secretKey: "9e769699fae6f594beafb46e9078c2"

) {

firstName

lastName

}

}mutation {

createUser(

user: {

firstName: "John"

lastName: "Rest"

username: "rest4eva"

email: "[email protected]"

authId: "github|2"

}

secretKey: "9e769699fae6f594beafb46e9078c2"

) {

firstName

lastName

}

}Now we can use the mongo shell to mark John Rest deleted and John Smith suspended:

$ mongo

> use guide

> db.users.updateOne({ username: 'rest4eva' }, { $set: { deletedAt: new Date() } })

{ "acknowledged" : true, "matchedCount" : 1, "modifiedCount" : 1 }

> db.users.updateOne({ username: 'jsmith' }, { $set: { suspendedAt: new Date(), durationInDays: 300, reason: 'Terms of Service violation' } })

{ "acknowledged" : true, "matchedCount" : 1, "modifiedCount" : 1 }Now let’s go back to our code—our resolver returns a list of users:

this.collection.find({ $text: { $search: term } }).toArray()But we don’t want all of the returned objects to be of type User—then the client would get the user data of the deleted/suspended users and not know they were deleted/suspended. Whenever we use a union type, we need to tell Apollo which objects are of which type. For that we use a special resolver called __resolveType:

export default {

Query: {

me:

user: ...

searchUsers: (_, { term }, { dataSources }) =>

dataSources.users.search(term)

},

UserResult: {

__resolveType: result => {

if (result.deletedAt) {

return 'DeletedUser'

} else if (result.suspendedAt) {

return 'SuspendedUser'

} else {

return 'User'

}

}

},Now when we return an object from a resolver that’s supposed to return a UserResult, Apollo gives that object to UserResult.__resolveType(), which returns the type of the object. So now the server can’t return the firstName of a deleted user, because it’s not a field of DeletedUser in the schema.

The last piece we need to add is SuspendedUser.daysLeft, which isn’t stored in the database (we only store suspendedAt and durationInDays in the database). So we create a resolver for it:

import { addDays, differenceInDays } from 'date-fns'

export default {

Query: ...

UserResult: ...

SuspendedUser: {

daysLeft: user => {

const end = addDays(user.suspendedAt, user.durationInDays)

return differenceInDays(end, new Date())

}

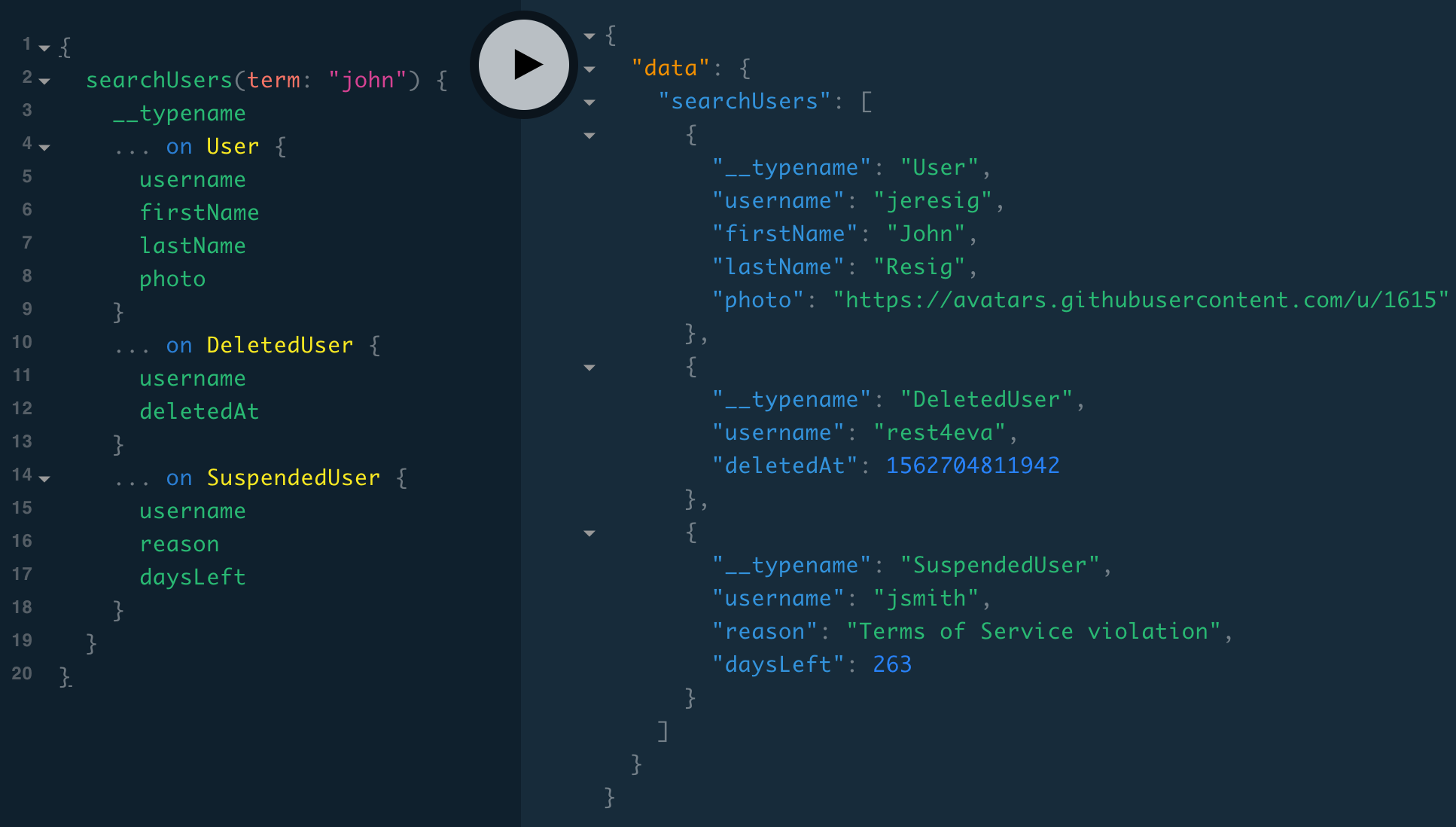

},addDays returns a date, and differenceInDays returns an integer. Now we can make our query:

{

searchUsers(term: "john") {

__typename

... on User {

username

firstName

lastName

photo

}

... on DeletedUser {

username

deletedAt

}

... on SuspendedUser {

username

reason

daysLeft

}

}

}

Even though

usernameis common to all possible types, with unions, the only field we can select outside of an inline fragment is the meta field__typename.

Now the client can iterate over data.searchUsers and check the __typename, and if it’s a DeletedUser or SuspendedUser, display that user differently.

For more ways to structure errors, check out Marc-André’s guide.

formatError

There’s an Apollo Server option called formatError that allows us to log and modify errors. In this section we’ll see a couple situations in which we might use it.

Logging errors

Background: Json Web Tokens

If you’re jumping in here,

git checkout 13_0.2.0(tag 13_0.2.0, or compare 13...14)

Usually when there are server errors, we see them in the errors field of the JSON response. In Playground, it’s usually easy to see all the error information, including the stack trace, but when it’s not easy to see the error on the client, it would be nice to be able to see the error in the server output on the command line. And in production we need some way of tracking the errors our users trigger.

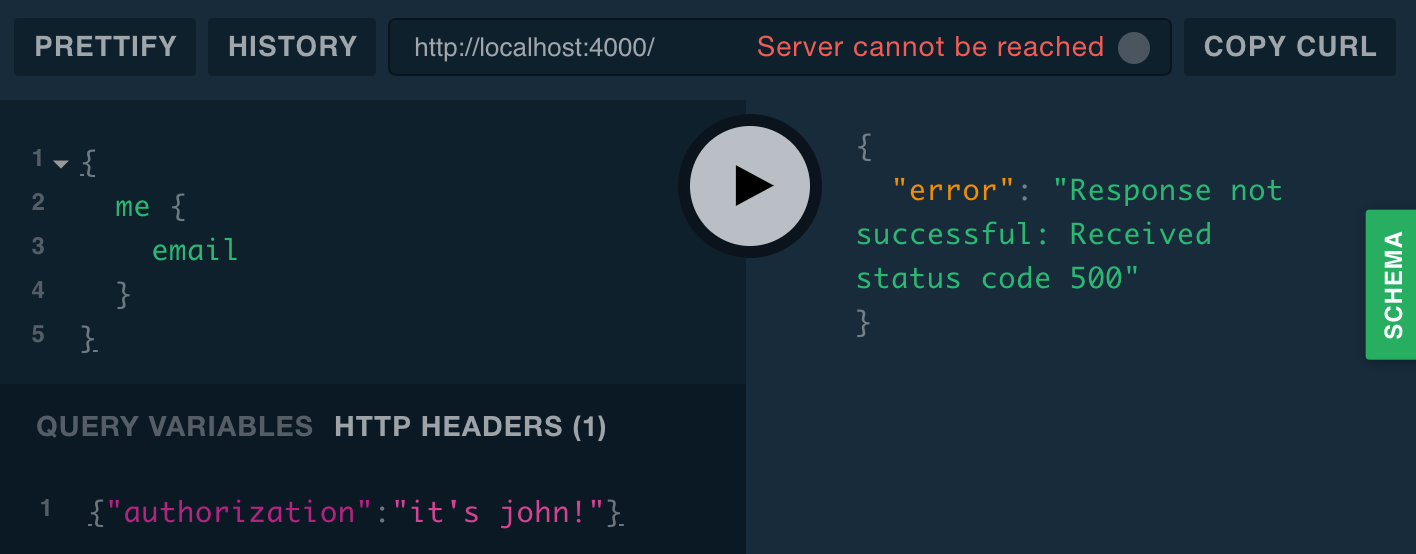

There is one case in which Playground doesn’t conveniently show us the server error: when it receives an error from an introspection query. Playground periodically sends an introspection query to our server to get an up-to-date schema to back its query checking and schema tab. When we set an HTTP header, Playground uses it for the introspection query as well. So when we set an invalid authorization header, the server returns an error for the introspection query, but Playground might not show it to us—it might just say “Response not successful”:

{

me {

email

}

}{

"authorization": "it's me, john!"

}

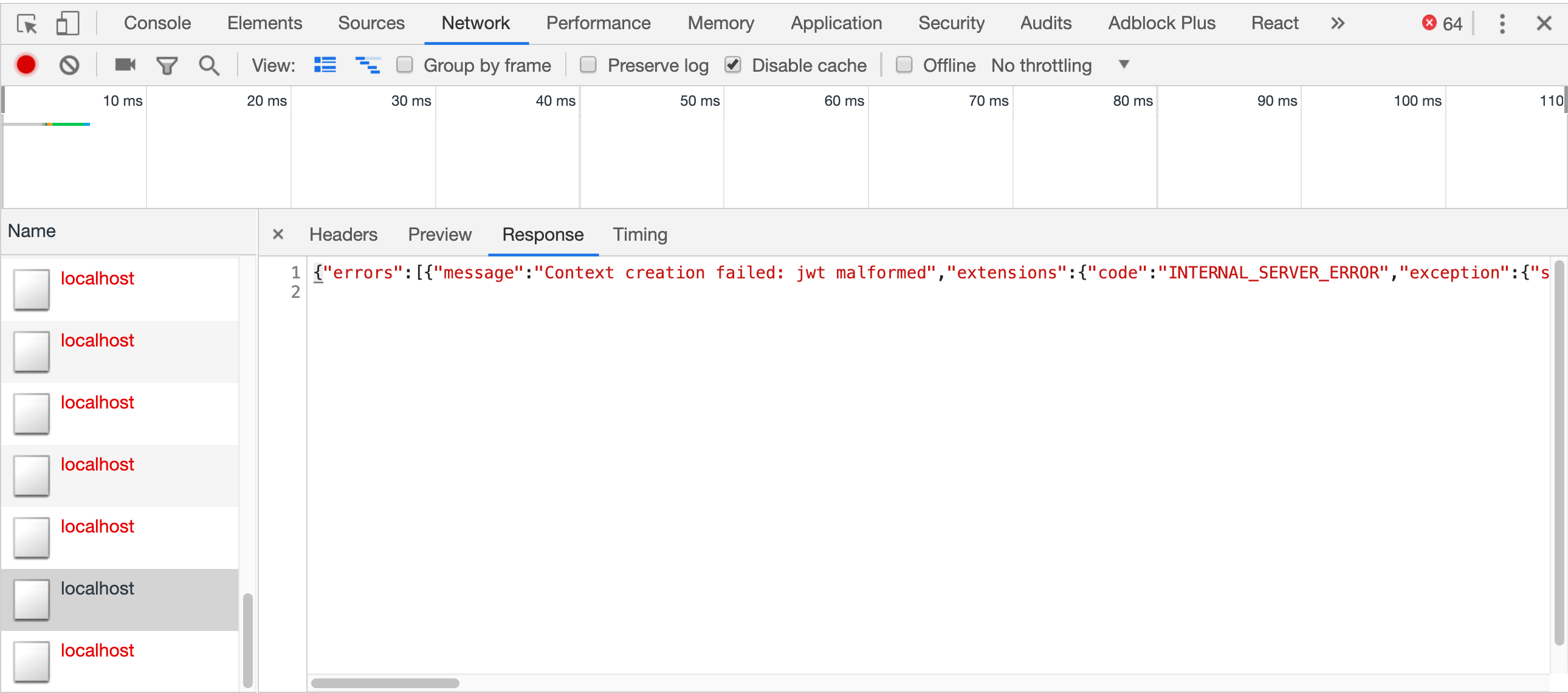

If we go into the devtools Network tab and select a localhost request, we can see the GraphQL errors field, but it’s hard to read the stack trace—we either have to scroll and visually parse the newlines or paste it into a JSON formatter (we recommend jq: brew install jq, copy, pbpaste | jq .).

Since that takes a few steps, let’s instead log the error using formatError:

import formatError from './formatError'

const server = new ApolloServer({

typeDefs,

resolvers,

dataSources,

context,

formatError

})export default error => {

console.log(error)

return error

}Now the error is logged to the terminal:

{ [JsonWebTokenError: Context creation failed: jwt malformed]

message: 'Context creation failed: jwt malformed',

locations: undefined,

path: undefined,

extensions:

{ code: 'INTERNAL_SERVER_ERROR',

exception: { stacktrace: [Array] } } }But we don’t see the stack trace, so let’s log that as well, if the error has one:

import get from 'lodash/get'

export default error => {

console.log(error)

console.log(get(error, 'extensions.exception.stacktrace'))

return error

}And now we also get:

[ 'JsonWebTokenError: Context creation failed: jwt malformed',

' at module.exports (/guide-api/node_modules/jsonwebtoken/verify.js:63:17)',

' at internal/util.js:230:26',

' at verify (/guide-api/src/util/auth.js:24:31)',

' at ApolloServer._default [as context] (/guide-api/src/context.js:8:24)',

' at ApolloServer.<anonymous> (/guide-api/node_modules/apollo-server-core/src/ApolloServer.ts:535:24)',

' at Generator.next (<anonymous>)',

' at /guide-api/node_modules/apollo-server-core/dist/ApolloServer.js:7:71',

' at new Promise (<anonymous>)',

' at __awaiter (/guide-api/node_modules/apollo-server-core/dist/ApolloServer.js:3:12)',

' at ApolloServer.graphQLServerOptions (/guide-api/node_modules/apollo-server-core/dist/ApolloServer.js:316:16)' ]And we can further debug! The error starts in node_modules/ (/guide-api/node_modules/jsonwebtoken/verify.js:63:17), so let’s look for the first lines that are inside our code (src/):

' at verify (/guide-api/src/util/auth.js:24:31)',

' at ApolloServer._default [as context] (/guide-api/src/context.js:8:24)',Now let’s look at src/context.js:

import { getAuthIdFromJWT } from './util/auth'

import { db } from './db'

export default async ({ req }) => {

const context = {}

const jwt = req.headers.authorization

const authId = await getAuthIdFromJWT(jwt)

const user = await db.collection('users').findOne({ authId })

if (user) {

context.user = user

}

return context

}Line 8 is const authId = await getAuthIdFromJWT(jwt). So the error message "jwt malformed" means the authorization header is not formatted as a valid JWT.

We achieved our goal of using formatError to log the error so that we could debug it. We can’t prevent clients from sending bad authorization headers, but we can improve the errors we throw. The two most common errors thrown during JWT parsing are jwt malformed and jwt expired, so let’s cover those:

import { AuthenticationError } from 'apollo-server'

export default async ({ req }) => {

const context = {}

const jwt = req.headers.authorization

let authId

if (jwt) {

try {

authId = await getAuthIdFromJWT(jwt)

} catch (e) {

let message

if (e.message.includes('jwt expired')) {

message = 'jwt expired'

} else {

message = 'malformed jwt in authorization header'

}

throw new AuthenticationError(message)

}

const user = await db.collection('users').findOne({ authId })

context.user = user

}

return context

}We catch errors from getAuthIdFromJWT(), and use a different error message depending on the kind of error. Then we use Apollo’s AuthenticationError error type, which adds an extensions.code of "UNAUTHENTICATED" to the error. The other errors that might occur are from the database (during the findOne())—we’ll cover these in the next section. Let’s also throw an error when there is no matching user in the database:

export default async ({ req }) => {

const context = {}

const jwt = req.headers.authorization

let authId

if (jwt) {

...

const user = await db.collection('users').findOne({ authId })

if (user) {

context.user = user

} else {

throw new AuthenticationError('no such user')

}

}

return context

}Now let’s repeat our bad-header query and see what new error we get in the console:

{ [AuthenticationError: Context creation failed: malformed jwt in authorization header]

message: 'Context creation failed: malformed jwt in authorization header',

locations: undefined,

path: undefined,

extensions: { code: 'UNAUTHENTICATED', exception: { stacktrace: [Array] } } }

[ 'AuthenticationError: Context creation failed: malformed jwt in authorization header',

' at ApolloServer._default [as context] (/Users/me/gh/guide-api/src/context.js:21:13)',

' at <anonymous>',

' at runMicrotasksCallback (internal/process/next_tick.js:121:5)',

' at _combinedTickCallback (internal/process/next_tick.js:131:7)',

' at process._tickCallback (internal/process/next_tick.js:180:9)' ]We now see the UNAUTHENTICATED error code and the more detailed error message. Our piece of the message—malformed jwt in authorization header—is preceded by Context creation failed:, which is added by Apollo for any errors that occur in the context function, and AuthenticationError:, which is taken from the name of the error object.

Masking errors

If you’re jumping in here,

git checkout 14_0.2.0(tag 14_0.2.0, or compare 14...15)

formatError() isn’t just for logging—as the name indicates, we can change the error. The most common change is masking an error we don’t want the client to see.

You may have noticed that we return the error in the last line of the formatError() function:

export default error => {

console.log(error)

console.log(get(error, 'extensions.exception.stacktrace'))

return error

}When an error is thrown in our code, Apollo catches it and gives it to formatError(), which returns an error object, which Apollo serializes into JSON and sends in the errors attribute to the client. Inside formatError(), we can modify the error object—by editing, adding, or removing properties—or return a new error.

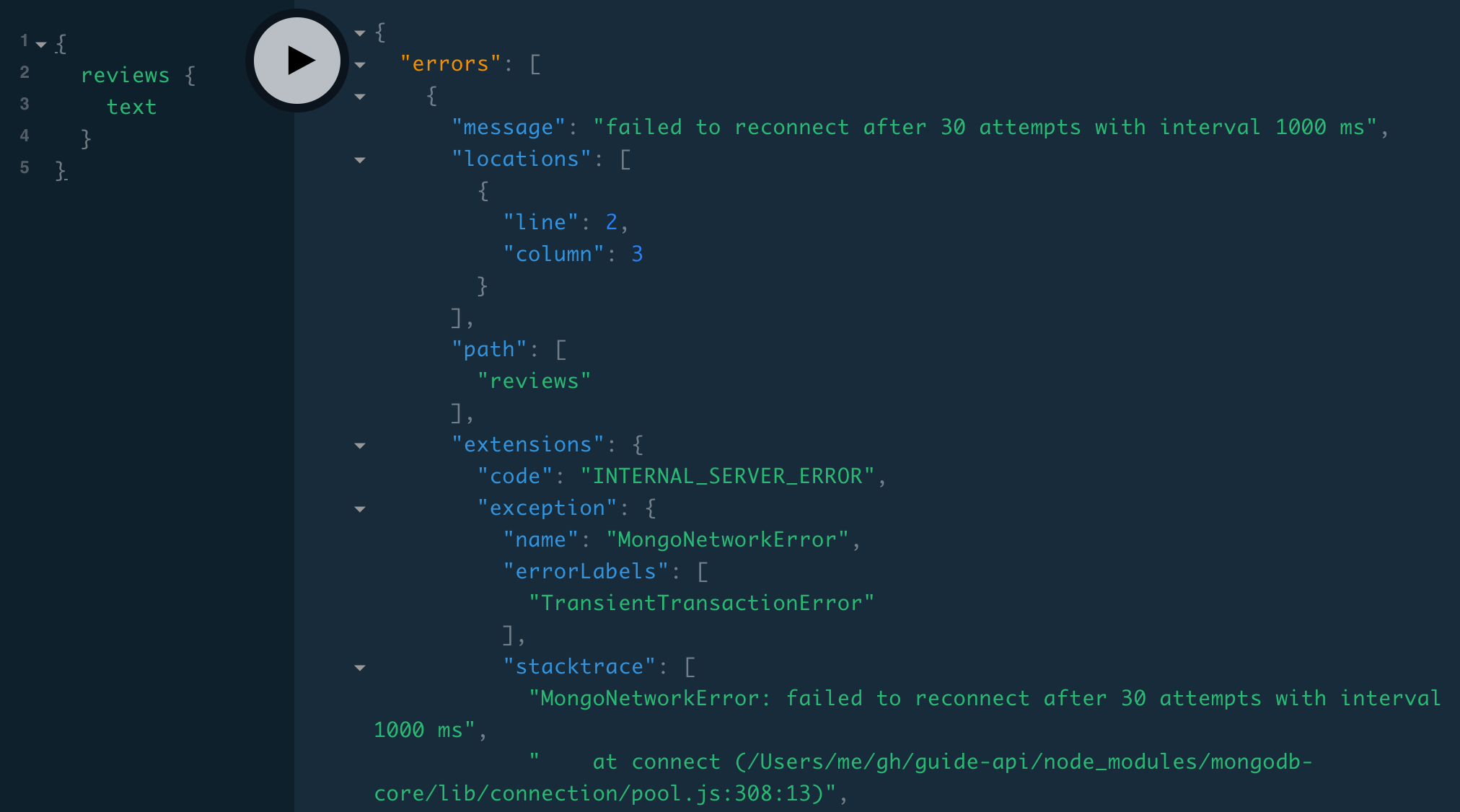

A common category of error to mask is database errors—we might want to hide the original error message for security reasons or to avoid confusing non-technical users with messages they don’t understand. Let’s see, for example, what errors happen when the server can’t reach the database. We can stop the database with this command:

$ brew services stop mongodb-communityIf we wait 30 seconds and then make a request, we get a MongoNetworkError:

And if we keep making requests, we start getting "MongoError: Topology was destroyed":

Let’s mask both of those with a new error:

export default error => {

console.log(error)

console.log(get(error, 'extensions.exception.stacktrace'))

const name = get(error, 'extensions.exception.name') || ''

if (name.startsWith('Mongo')) {

return new Error('Internal server error')

} else {

return error

}

}When we edit our code, the server fails to restart because it can’t connect to the database. So in order to test, we can restart Mongo:

$ brew services start mongodb-communityAnd then restart the server, and then stop Mongo:

$ brew services stop mongodb-communityNow we get our masked error instead of either of the Mongo errors:

One last note on formatError—in production, we’ll usually want to send our errors to an error tracking or logging service instead of logging them to the server console:

const inProduction = process.env.NODE_ENV === 'production'

export default error => {

if (inProduction) {

// send error to tracking service

} else {

console.log(error)

console.log(get(error, 'extensions.exception.stacktrace'))

}

...

}Error checking

If you’re jumping in here,

git checkout 15_0.2.0(tag 15_0.2.0, or compare 15...16)

So far we’ve dealt with the User.email authorization error, users who have been deleted or suspended, authentication errors, and MongoDB errors. Let’s go through our entire app and think about all the possible errors we want to handle or throw:

- Network: If our node server is cut off from the internet, or if there’s a DNS issue, the client won’t be able to connect to our server, and will see an error that will look different depending on their browser or platform.

- Servers

- Node: If our Node GraphQL application server isn’t running, then the client won’t be able to connect, and will see the same error as when there’s a network failure.

- MongoDB: We mask errors with our MongoDB server, including inability to connect, in

formatError()

- Request: If the network request isn’t a valid GraphQL HTTP request, then the error will be handled before it reaches our code—either by our server’s operating system, Node, or Apollo Server.

- Context: Assuming the request is a valid GraphQL request (including valid against our schema), the server starts by setting the context for resolvers. This process often involves looking at request headers. We covered errors that might occur while creating context in the Logging errors section.

- Resolvers:

- Arguments: Apollo validates the arguments’ data types, but we often want to do further validation on the argument values.

- Execution: We want to handle any possible errors that might occur in the running of our resolver code—things like invalid JWT decoding, dividing by zero, or trying to access a 3rd party service that’s offline.

- Authorization: If there’s data or functions that we don’t want certain people to access or trigger, we need to avoid returning the data / running the functions.

In this section we’ll go through our resolvers. Let’s start with authorization. For data access, let’s look at our main data types:

type Review {

id: ID!

author: User!

text: String!

stars: Int

fullReview: String!

createdAt: Date!

updatedAt: Date!

}

type User {

id: ID!

firstName: String!

lastName: String!

username: String!

email: String

photo: String!

createdAt: Date!

updatedAt: Date!

}Depending on our app, we might consider createdAt and updatedAt to be sensitive, but for us, the only field we don’t want to be public is email, which we already have a check for. If we had an app for which an entire data type was restricted, then in order to verify it was restricted properly, we would need to search for that type everywhere it was referenced in the schema and make sure those queries, mutations, or other fields were restricted. For instance, if we only wanted logged-in users to be able to view user data, then we’d look for User in the above and below parts of the schema:

type Query {

hello(date: Date): String!

isoString(date: Date!): String!

reviews: [Review!]!

me: User

user(id: ID!): User

searchUsers(term: String!): [UserResult!]!

}

type Mutation {

createReview(review: CreateReviewInput!): Review

createUser(user: CreateUserInput!, secretKey: String!): User

}We would need to restrict Review.author, Query.user, and Query.searchUsers, and make sure that:

Query.me, which returns aUser, only returns the current user.Mutation.createUser, which also returns aUser, doesn’t return any user but the one just created by that client.

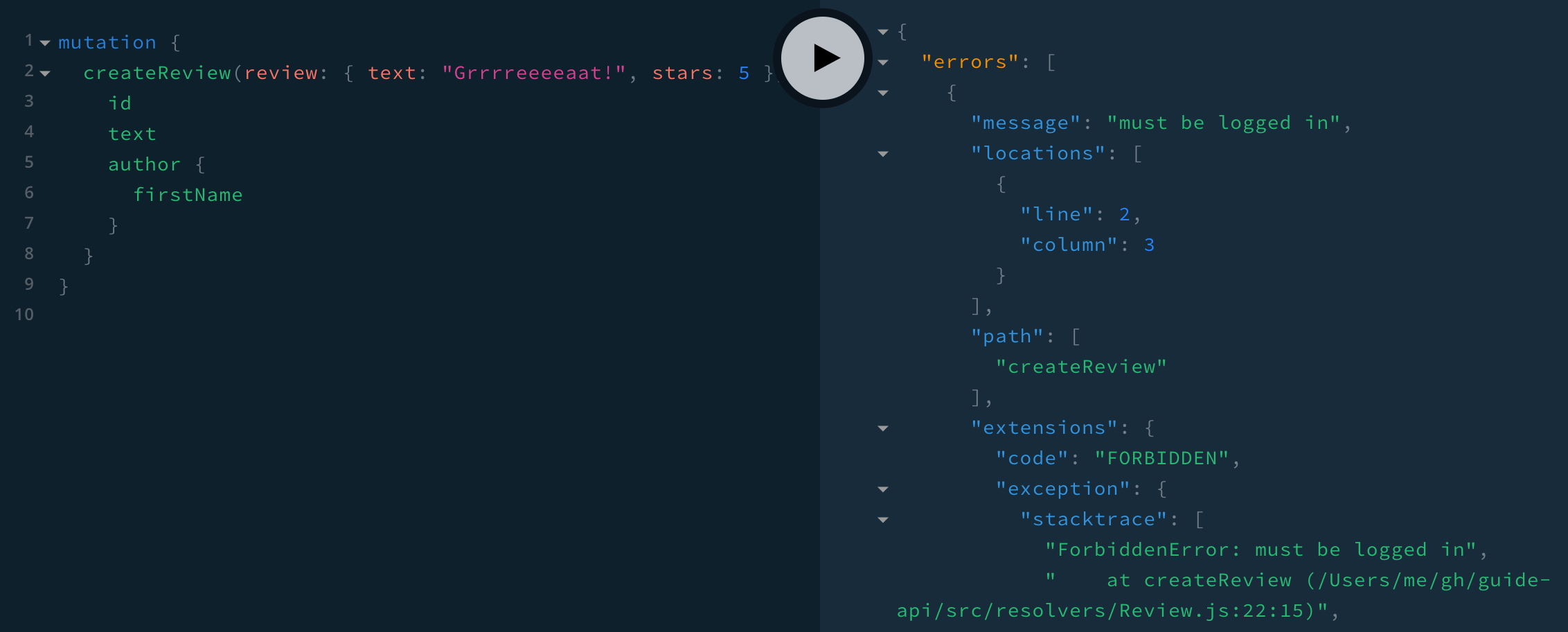

That’s all for authorization on data access. The other part is authorization on running functions—specifically, functions that change things. While it’s possible for a Query resolver function to change something, it’s better to make those functions Mutations. Let’s assume we’ve defined our Query and Mutation types properly, and haven’t accidentally modified data in our Query resolvers. That means we only need to check our mutations, createReview and createUser. createUser we already protected with a secretKey. createReview can currently be run by anyone, but we want it to be run only by logged-in users. Let’s fix that:

import { ForbiddenError } from 'apollo-server'

export default {

Query: ...

Review: ...

Mutation: {

createReview: (_, { review }, { dataSources, user }) => {

if (!user) {

throw new ForbiddenError('must be logged in')

}

dataSources.reviews.create(review)

}

}

}Now when we try the mutation without an authorization header, we get an error with the message "must be logged in" and code "FORBIDDEN":

mutation {

createReview(review: { text: "Grrrreeeeaat!", stars: 5 }) {

id

text

author {

firstName

}

}

}

That concludes authorization in resolvers. Next let’s check arguments. First we look back at the schema and think about which Query arguments need further validation:

type Query {

hello(date: Date): String!

isoString(date: Date!): String!

reviews: [Review!]!

me: User

user(id: ID!): User

searchUsers(term: String!): [UserResult!]!

}We don’t need to do anything with the first two queries—our custom scalar checks validity, and any valid date is fine for those queries. The third and fourth don’t have arguments. The last two do. Here’s what they currently look like:

export default {

Query: {

me: ...

user: (_, { id }, { dataSources }) =>

dataSources.users.findOneById(ObjectId(id)),

searchUsers: (_, { term }, { dataSources }) =>

dataSources.users.search(term)

},

...

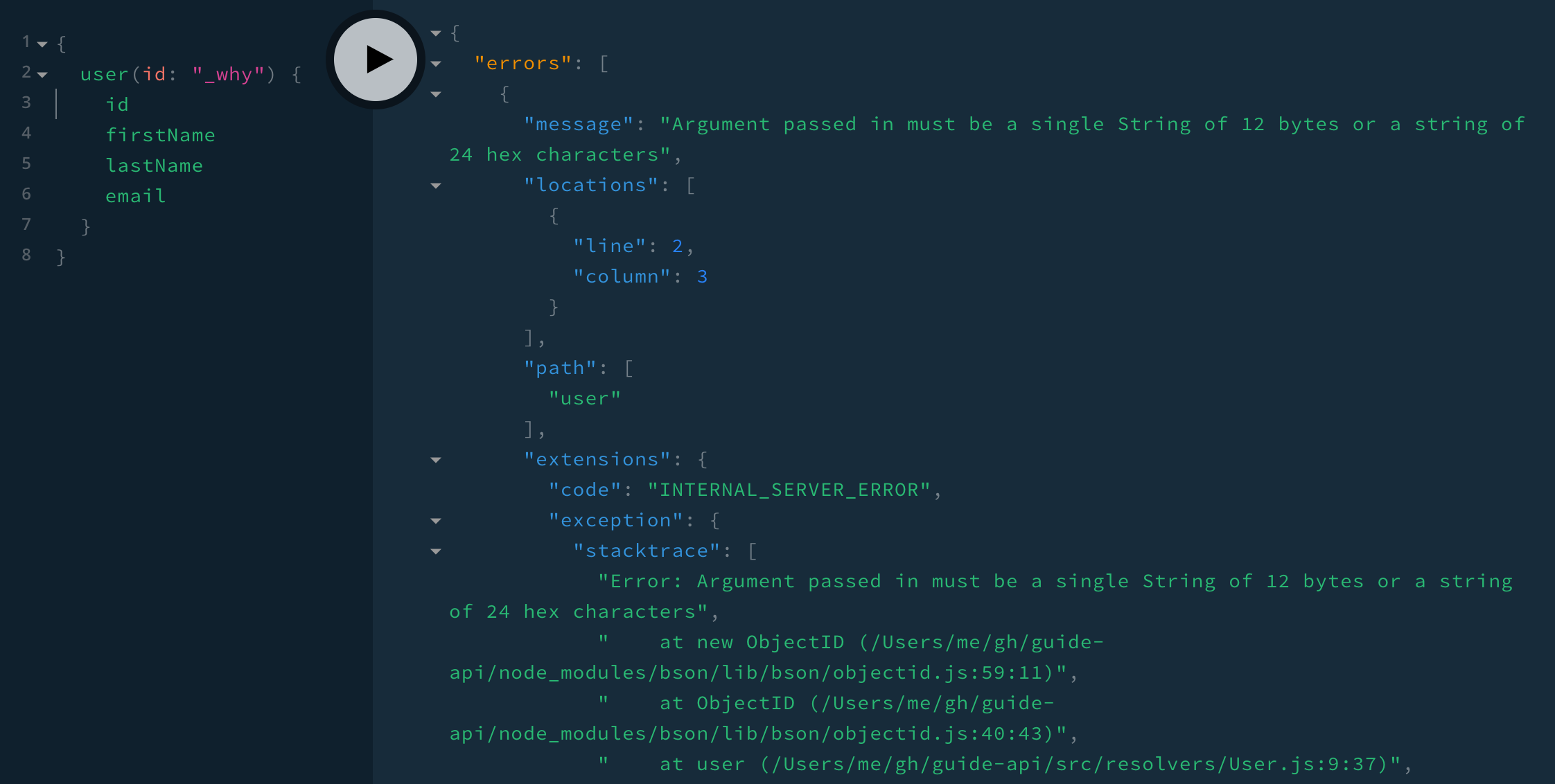

}Searching with an empty string gives back an empty list, which is fine. We also don’t need to worry about a NoSQL injection attack with a text search. So let’s leave the searching to handle any string, blank or malicious, and move on to Query.user. Any string validates as an ID, so let’s see what happens when we try to get a user with an ID of '_why':

{

user(id: "_why") {

firstName

}

}

We get an error with the message "Argument passed in must be a single String of 12 bytes or a string of 24 hex characters" and code "INTERNAL_SERVER_ERROR". We can tell from the stack trace that it’s coming from our ObjectId(id) call, but it may very well be confusing to the client. Let’s help the client out by giving them a better error message:

import { UserInputError } from 'apollo-server'

const OBJECT_ID_ERROR =

'Argument passed in must be a single String of 12 bytes or a string of 24 hex characters'

export default {

Query: {

me: ...

user: (_, { id }, { dataSources }) => {

try {

return dataSources.users.findOneById(ObjectId(id))

} catch (error) {

if (error.message === OBJECT_ID_ERROR) {

throw new UserInputError('invalid id', {

invalidArgs: ['id']

})

} else {

throw error

}

}

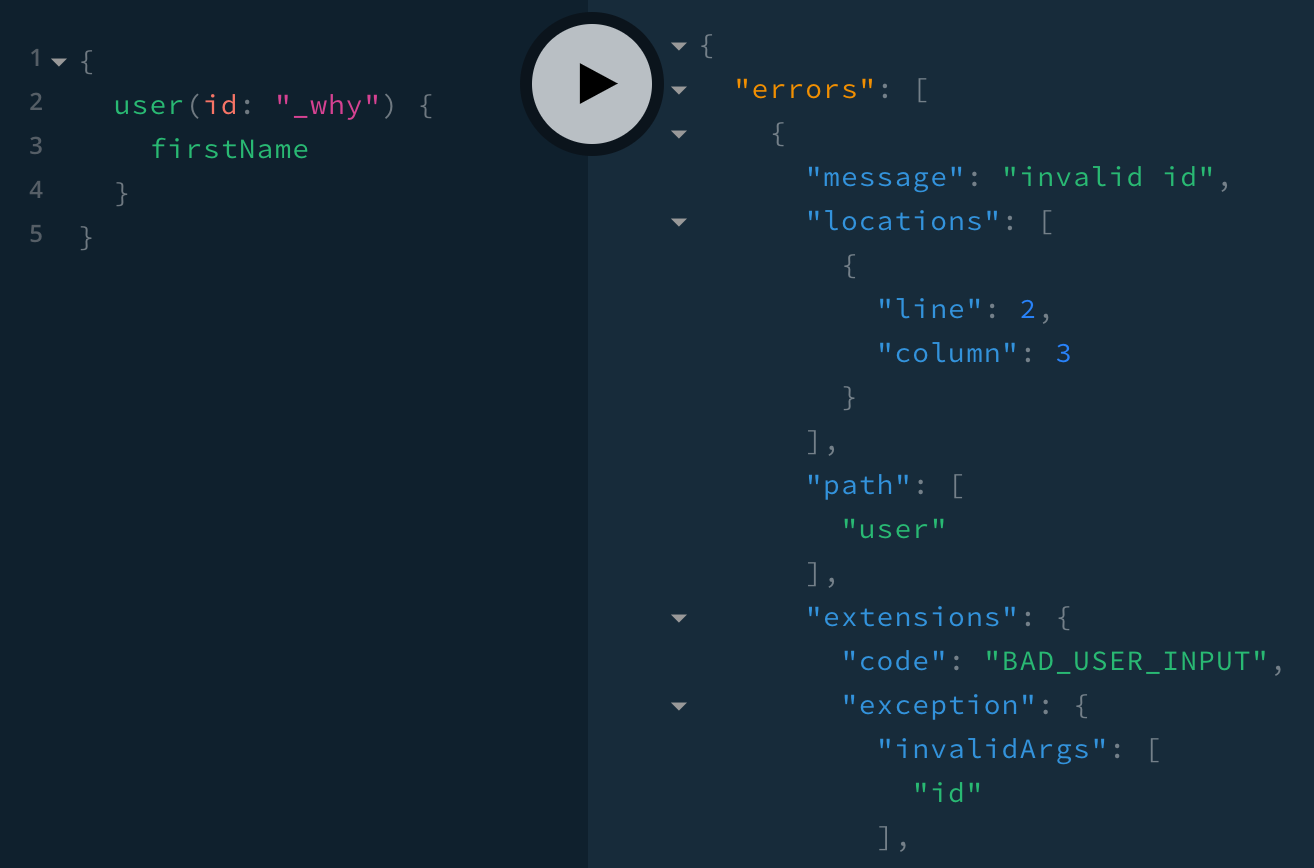

},We use another built-in error type called UserInputError, which sets extensions.code to BAD_USER_INPUT and lists the invalid arguments in extensions.invalidArgs:

We’re done checking Query arguments. Now let’s do Mutation arguments:

type Mutation {

createUser(user: CreateUserInput!, secretKey: String!): User

createReview(review: CreateReviewInput!): Review

}Because of secretKey, we can trust that our own code is the only one calling createUser. Let’s also trust that our code sends good data for the user argument, so we can leave that resolver alone. Lastly is createReview with CreateReviewInput:

input CreateReviewInput {

text: String!

stars: Int

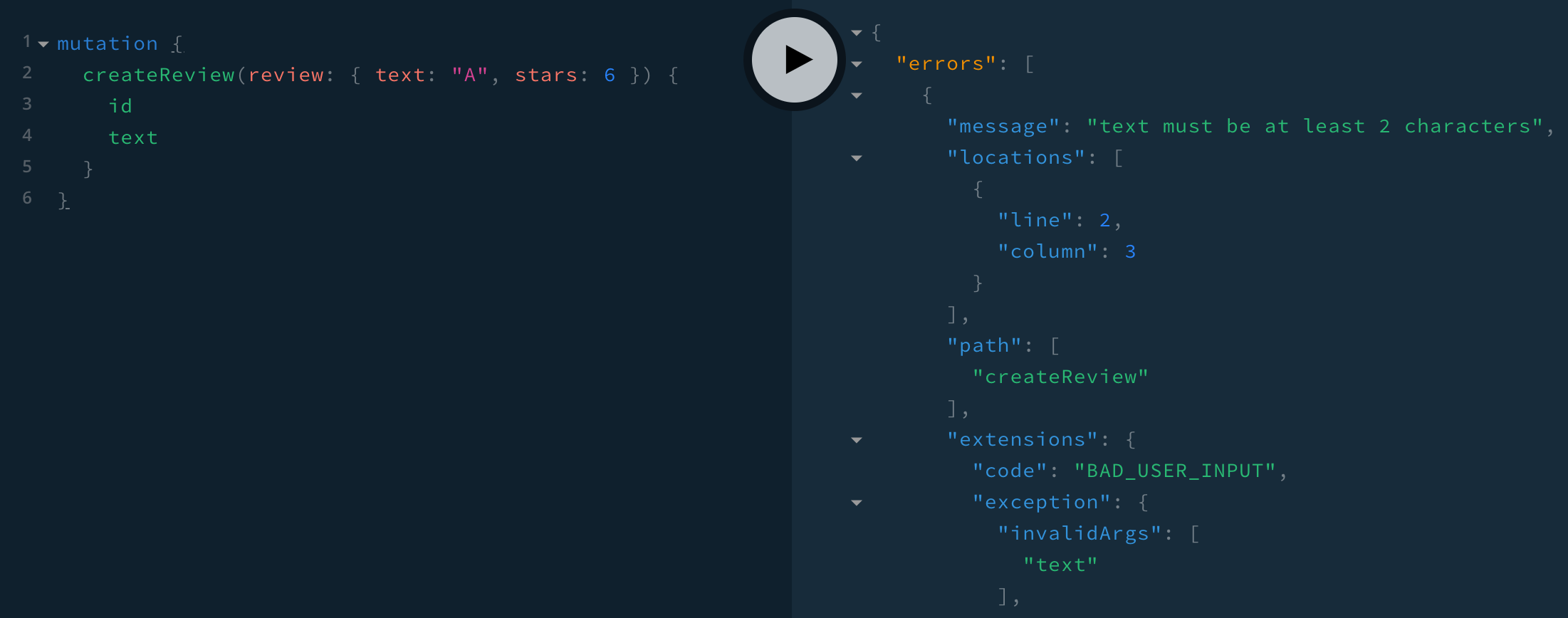

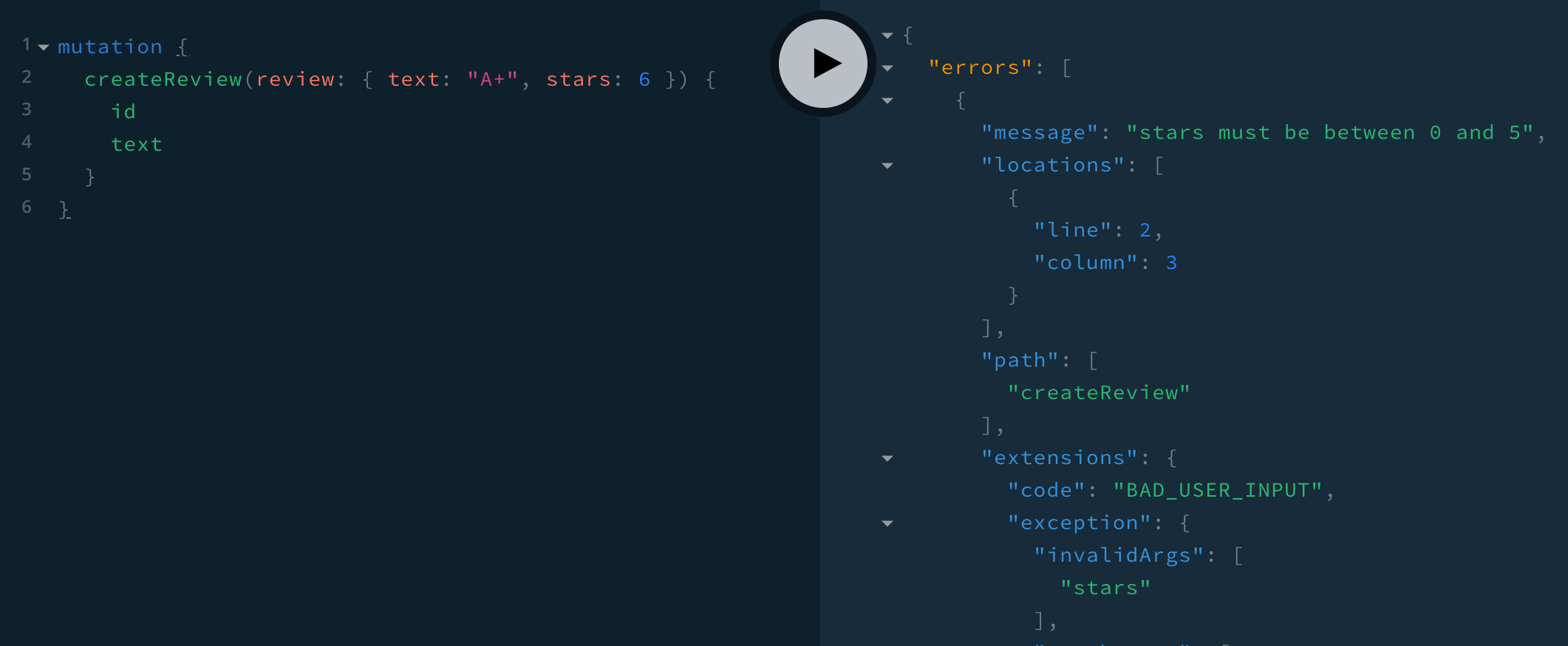

}Inside our resolver, we can trust that review.text is a string and that review.stars is either undefined or an integer. We need to further check that review.text is a valid length (let’s say at least two characters 😄) and that review.stars is between 0 and 5.

import { ForbiddenError, UserInputError } from 'apollo-server'

const MIN_REVIEW_LENGTH = 2

const VALID_STARS = [0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

export default {

Query: ...

Review: ...

Mutation: {

createReview: (_, { review }, { dataSources, user }) => {

if (!user) {

throw new ForbiddenError('must be logged in')

}

if (review.text.length < MIN_REVIEW_LENGTH) {

throw new UserInputError(

`text must be at least ${MIN_REVIEW_LENGTH} characters`,

{ invalidArgs: ['text'] }

)

}

if (review.stars && !VALID_STARS.includes(review.stars)) {

throw new UserInputError(`stars must be between 0 and 5`, {

invalidArgs: ['stars']

})

}

return dataSources.reviews.create(review)

}

}

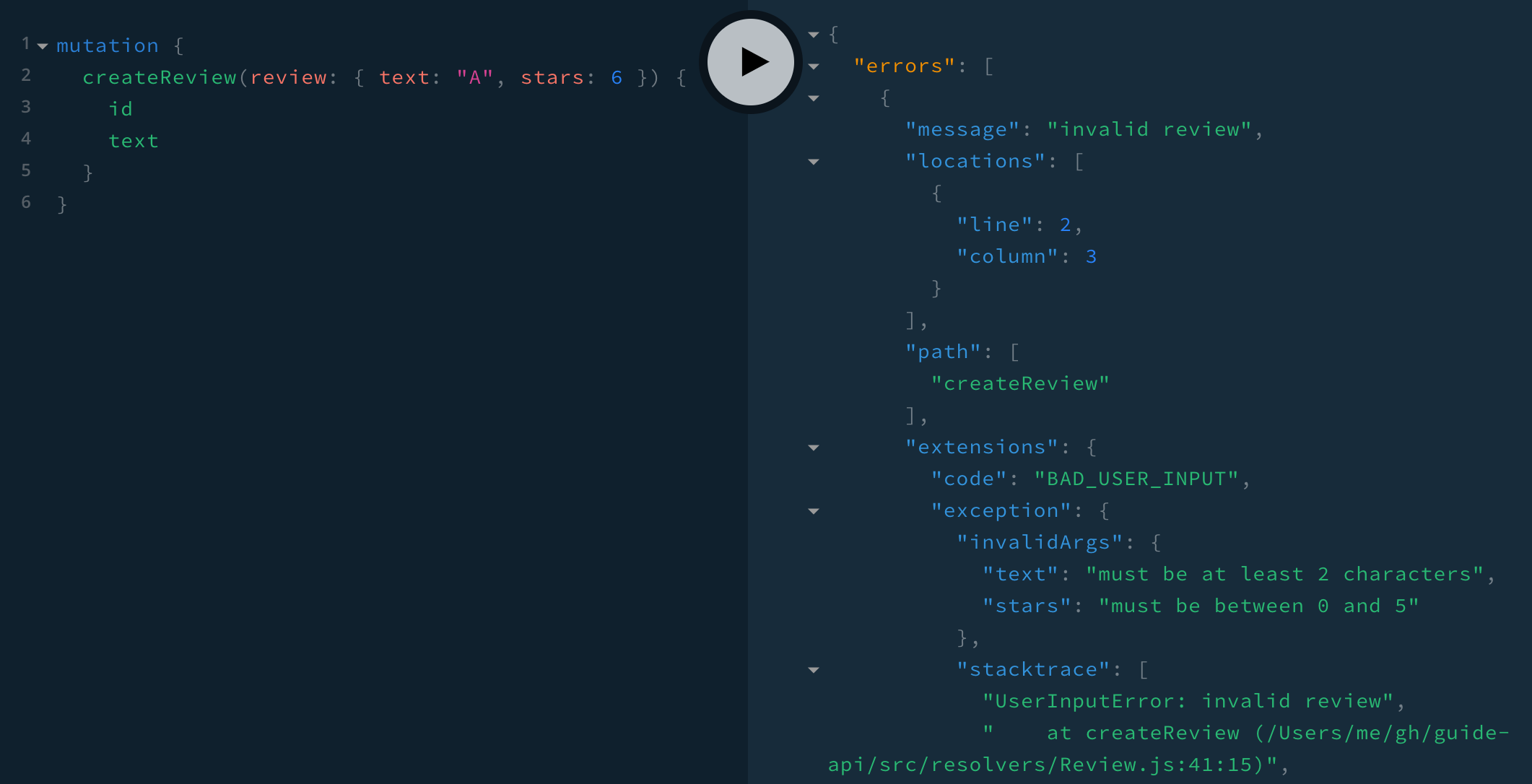

}Since CreateReviewInput! is non-null, we don’t have to check that review is defined. Similarly, we don’t have to check that review.text is defined. Let’s check both errors:

mutation {

createReview(review: { text: "A", stars: 6 }) {

id

text

}

}

That’s all of our input validation, and the last of our error checking! ✅

Custom errors

If you’re jumping in here,

git checkout 16_0.2.0(tag 16_0.2.0, or compare 16...17)

In addition to the built-in UserInputError, ForbiddenError, and AuthenticationError that we’ve used, there’s also their superclass, ApolloError, which we can use directly to add arbitrary error data or extend to make our own error classes. We’ll do both in this section.

In the last section, when checking the review argument to createReview, we threw an error for either review.text or review.stars. If both were incorrect, the client would just get the first error, for review.text. Once the client fixed that and tried again, they would then get the review.stars error. It would be helpful to the client if we can give both errors at the same time.

We could do { invalidArgs: ['text', 'stars'] } and combine the two error messages into one message, but it would be better to associate each error message with the corresponding argument—that way, for instance, the client can display individual error messages next to each invalid form field. It turns out that UserInputError takes any object as its second argument (and adds it to the response JSON’s extensions.exception). Let’s keep the recommended invalidArgs attribute, but change the value from an array to an object:

{

invalidArgs: {

text: 'must be at least 2 characters',

stars: 'must be between 0 and 5'

}

}To get this, we update the code to:

import { isEmpty } from 'lodash'

export default {

Query: ...

Review: ...

Mutation: {

createReview: (_, { review }, { dataSources, user }) => {

if (!user) {

throw new ForbiddenError('must be logged in')

}

const errors = {}

if (review.text.length < MIN_REVIEW_LENGTH) {

errors.text = `must be at least ${MIN_REVIEW_LENGTH} characters`

}

if (review.stars && !VALID_STARS.includes(review.stars)) {

errors.stars = `must be between 0 and 5`

}

if (!isEmpty(errors)) {

throw new UserInputError('invalid review', { invalidArgs: errors })

}

return dataSources.reviews.create(review)

}

}

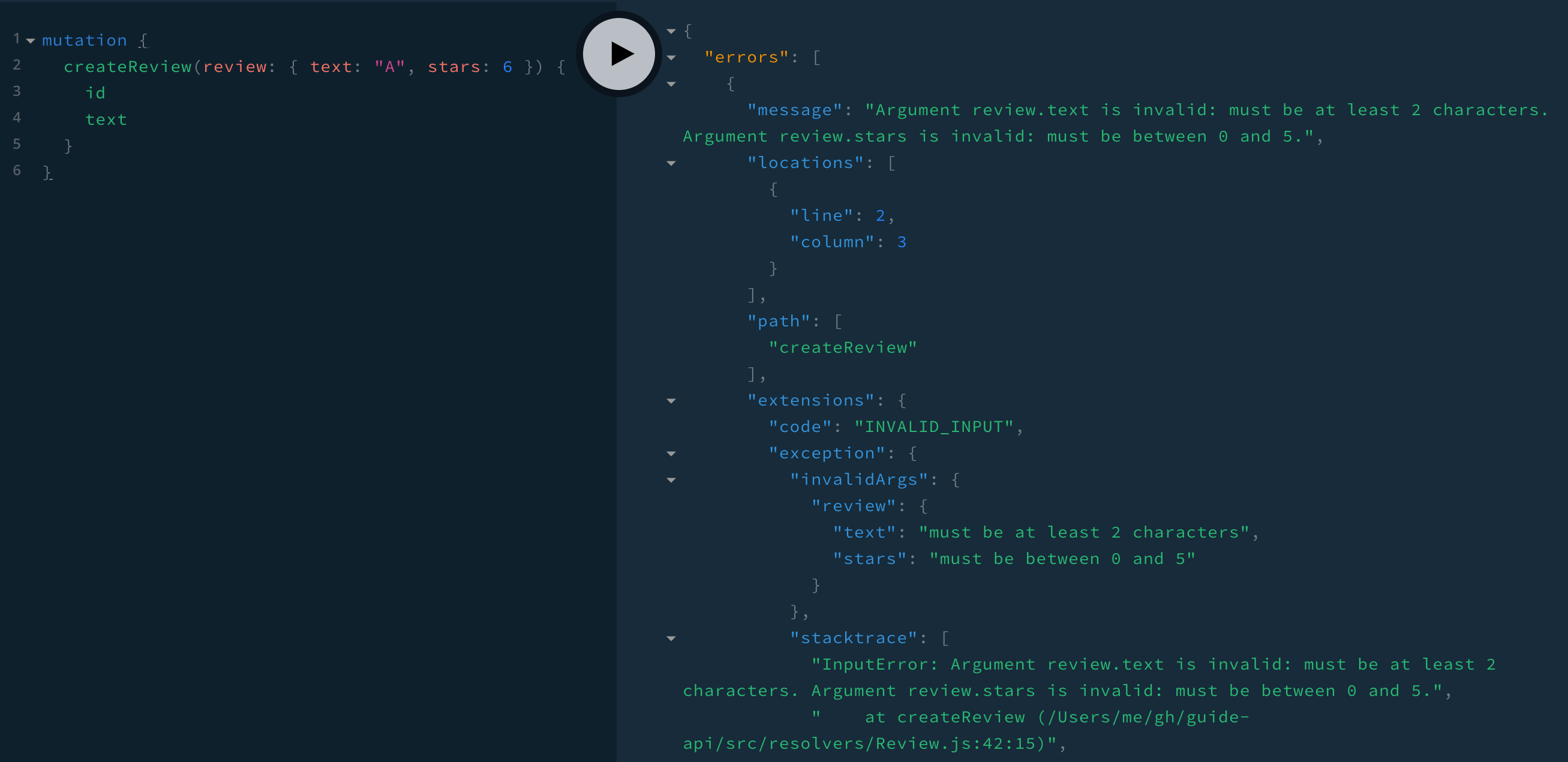

}Now we see both errors together!

mutation {

createReview(review: { text: "A", stars: 6 }) {

id

text

}

}

We use UserInputError in one other place. Let’s update the invalidArgs format there as well to be consistent so that the client can easily programmatically work with extensions.exception.invalidArgs:

if (error.message === OBJECT_ID_ERROR) {

throw new UserInputError('invalid id', {

invalidArgs: { id: 'not a valid Mongo ObjectId' }

})

}We’ll come back to UserInputError in a bit. For now let’s consider this from src/formatError.js:

return new Error('Internal server error')The resulting response is bare, without even a stack trace:

Apollo only adds the extensions field (including a stack trace in development) for ApolloError and its subclasses. So let’s use that:

import { ApolloError } from 'apollo-server'

...

if (name.startsWith('Mongo')) {

return new ApolloError(

`We’re sorry—an error occurred. We’ve been notified and will look into it.`,

'INTERNAL_SERVER_ERROR'

)

} else {

return error

}

ApolloError takes three arguments: the error message, a code, and additional properties to add to extensions.exception. We’re using the first two. Having a code makes it easy for the client to handle all internal server errors similarly. Having a user-friendly message means that the client can show it directly to the user.

In case we want to throw an internal server error elsewhere in the future, let’s make our own InternalServerError class:

import { ApolloError } from 'apollo-server'

export class InternalServerError extends ApolloError {

constructor() {

super(

`We’re sorry—an error occurred. We’ve been notified and will look into it.`,

'INTERNAL_SERVER_ERROR'

)

Object.defineProperty(this, 'name', { value: 'InternalServerError' })

}

}super() gets the same arguments that the ApolloError() constructor got. The last thing is setting the object’s name, which is used at the beginning of the stack trace. Now our use of the error can be simplified:

import { InternalServerError } from './util/errors'

...

if (name.startsWith('Mongo')) {

return new InternalServerError()

} else {

return error

}

}Let’s also make a custom input error. Currently we’re using UserInputError like this:

import { UserInputError } from 'apollo-server'

...

if (!isEmpty(errors)) {

throw new UserInputError('invalid review', { invalidArgs: errors })

}It would be simpler if we had an InputError class that we could use like this:

import { InputError } from '../util/errors'

...

if (!isEmpty(errors)) {

throw new InputError({ review: errors })

}And then InputError could take care of the error message for us. We could also use it in our user resolver:

import { InputError } from '../util/errors'

export default {

Query: {

me: ...

user: (_, { id }, { dataSources }) => {

try {

return dataSources.users.findOneById(ObjectId(id))

} catch (error) {

if (error.message === OBJECT_ID_ERROR) {

throw new InputError({ id: 'not a valid Mongo ObjectId' })

} else {

throw error

}

}

},The only difference here is that our argument id is a scalar type, so we pass { id: 'not a valid Mongo ObjectId' } to InputError(), versus the review object type argument to createReview, which looked like:

{

review: {

text: 'must be at least 2 characters',

stars: 'must be between 0 and 5'

}

}So when we implement our InputError class, we have to cover both scenarios—scalar arguments and their messages, as well as object arguments and their invalid field messages. As before, we subclass ApolloError, but this time the constructor creates the error message:

export class InputError extends ApolloError {

constructor(errors) {

let messages = []

for (const arg in errors) {

if (typeof errors[arg] === 'string') {

// scalar argument

const errorReason = errors[arg]

messages.push(`Argument ${arg} is invalid: ${errorReason}.`)

} else {

// object argument

const errorObject = errors[arg]

for (const prop in errorObject) {

const errorReason = errorObject[prop]

messages.push(`Argument ${arg}.${prop} is invalid: ${errorReason}.`)

}

}

}

const fullMessage = messages.join(' ')

super(fullMessage, 'INVALID_INPUT', { invalidArgs: errors })

Object.defineProperty(this, 'name', { value: 'InputError' })

}

}Now when we make an invalid query, we see:

- a very detailed error

message - our own error code

INVALID_INPUT - a different

invalidArgsobject, from which we can tell what argument the fieldstextandstarsare on (review) - “InputError” at the beginning of the stack trace

In this section we went over:

- passing arbitrary

extensions.exceptionproperties as the second argument toUserInputError()(or the third argument ofApolloError()) - using

ApolloError()directly - creating our own error classes:

InternalServerErrorandInputError