Authorization

To view this content, buy the book! 😃🙏

Or if you’ve already purchased.

Authorization

If you’re jumping in here,

git checkout 10_0.2.0(tag 10_0.2.0, or compare 10...11)

In this section we’ll implement an authorization check for a field on the User type. Later, in the Error checking section, we’ll talk about how to find the places we need to do authorization checks.

Let’s first add a new user query for fetching a single user by id:

extend type Query {

me: User

user(id: ID!): User

}import { ObjectId } from 'mongodb'

export default {

Query: {

me: (_, __, context) => context.user,

user: (_, { id }, { dataSources }) =>

dataSources.users.findOneById(ObjectId(id))

},

User: ...

Mutation: ...We have to turn the id string we receive as an argument into an ObjectId before calling findOneById(). The alternative would be to create an ObjID custom scalar that parsed string arguments into ObjectId objects, and then if we changed the argument type from ID to ObjID, then the id argument would be an ObjectId object by the time it reached our resolver, and we could call findOneById() directly:

extend type Query {

me: User

user(id: ObjID!): User

} user: (_, { id }, { dataSources }) =>

dataSources.users.findOneById(id)import { GraphQLScalarType } from 'graphql'

import { ObjectId } from 'mongodb'

export default {

ObjID: new GraphQLScalarType({

name: 'ObjID',

description: ...

parseValue: value => ObjectId(value),

parseLiteral: ast => ObjectId(ast.value),

serialize: objectId => objectId.toString()

})

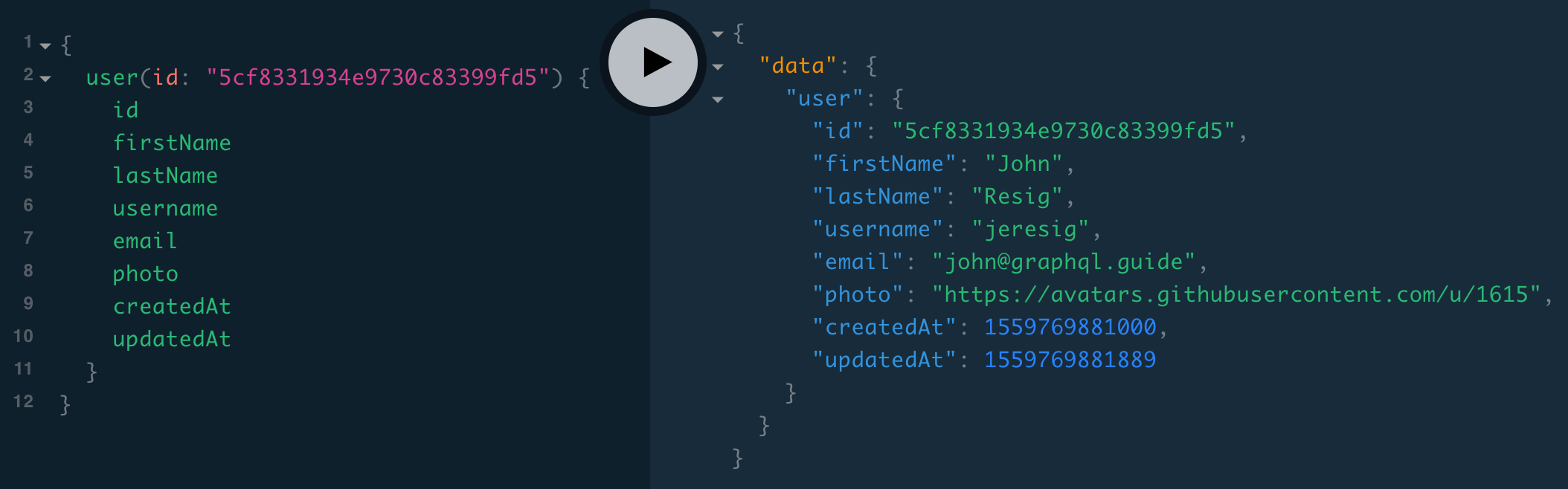

}Let’s try our new user query:

We might now notice an issue. This query works without being logged in (i.e., including an authorization header), and it returns the user’s email address. Similarly, we can query { reviews { author { email } } } without being logged in. Our users would probably prefer their email addresses to not be publicly available! 😄

There are a few possible ways to solve this issue:

- We could remove the

emailfield from theUsertype. However, it would be nice to be able to show users their own email address on their profile page. - We could check whether the user is fetching their own email.

We could do the check in three places:

- Resolver: we just add an if statement to the beginning of a

User.emailresolver function. - Data source: this doesn’t have the granularity of the

User.emailresolver. If we threw an error in the data source method, the client wouldn’t get any of the user’s data. Doing authorization checks in data sources works well for preventing access to whole objects: for instance, if we wanted to prevent clients from fetching any user but their own. It works particularly well when there are multiple places in the schema the user can be accessed from. Instead of doing the check both inQuery.userandReview.author, we can do it once in thefindOneById()method of theUsersdata source. - Schema: we can add a custom directive like @isCurrentUser:

type User {

id: ID!

firstName: String!

lastName: String!

email: String! @isCurrentUser

...

}(And we’d make more directives for other authorization checks, like @isLoggedIn to deny access to a field from anonymous clients or @isAdmin to only allow admins to access a field.)

Wherever we do the check, when the user being requested doesn’t match the logged-in user, we could either:

- Throw an error.

- Return

null. The upside is it’s easier for clients to handle than an error. (For example, if they query for 20 reviews with their authors, they’d get 20 errors to sort through.) The downside is they don’t know why they’re getting anullresponse—they might think the user just doesn’t have an email. - Use a union type that combines the normal result with the error result, like:

union EmailResult = Email | Forbidden

type Email {

address: String!

verified: Boolean!

}

type Forbidden {

message: String!

}

type User {

id: ID!

firstName: String!

lastName: String!

email: EmailResult!

...

}We’ll cover union errors in the next section.

In this case, let’s do the check in a resolver and throw an error. We currently don’t have a resolver for User.email, because Apollo Server just uses the email property on the user object. It does the equivalent of this tiny resolver:

{

User: {

email: user => user.email

...

}

}When we provide our own resolver, Apollo Server will call our resolver instead of automatically returning user.email. Here’s what our resolver looks like:

import { ForbiddenError } from 'apollo-server'

export default {

Query: {

me: (_, __, context) => context.user,

user: (_, { id }, { dataSources }) =>

dataSources.users.findOneById(ObjectId(id))

},

User: {

id: ({ _id }) => _id,

email(user, _, { user: currentUser }) {

if (!currentUser || !user._id.equals(currentUser._id)) {

throw new ForbiddenError(`cannot access others’ emails`)

}

return user.email

},

...

},

Mutation: ...

}We’d have a naming conflict if we destructured user from context, so we assign to a new variable name currentUser. First we test whether there’s any user at all, and then we test whether it’s the same user. In the next section we’ll see what the error looks like to the client! 👀